Winter has come and I’m not talking about the Melbourne’s frosty temperatures.

Frozen Shoulder or clinically known as Adhesive Capsulitis is a common shoulder condition that brings with it pain and progressive severe limitation to the mobility of the glenohumeral joint.

Some studies report over 90% of frozen shoulder patients notice pain before stiffness then progressing to a phase of increasing pain and stiffness, however pain is the predominant complaint in these cases (Hanchard et al. 2011).

Patients that present with frozen shoulder will commonly show signs and symptoms of the same condition in the opposing shoulder likely years after the original shoulder, however the good news is they will not present with Adhesive Capsulitis twice in the one shoulder (Jain & Sharma, 2014).

INCIDENCE

Some studies report 2-5% of the general population will experience Frozen Shoulder at some stage in their lives, making it incredibly common. When looking at specific population groups the incidence increases to 10-20% of people with diabetes and is most commonly contracted by woman more than men and most commonly in the people 50-60 years of age (Buchbinder et al. 2008)

The problem with these numbers is the difficulty in diagnosing the condition with no clear parameters for distinct diagnosis.

The overriding treatment of patients with a stiff and painful shoulder is to label them as having a frozen shoulder, however the specific nature of its history and resolution could not be more different to that of conditions such as subacromial impingement, rotator cuff tendinopathies or even osteoarthritis conditions of the glenohumeral joint.

Presentation / Diagnosis

Commonly referred to as an idiopathic type shoulder condition, meaning that the onset of symptoms is spontaneous without any history of trauma, shoulder injury or pre-existing condition. This has spurred authors in this area to sub-categorise it into two types of contracture or restriction, being Primary (without history of injury or trauma) and Secondary (known onset of injury or cause) (Jain et al 2014). This helps clinicians in an attempt to properly pick the treatment strategy for the individual patient as well as being able to give a proper prognosis or management plan.

Restriction in shoulder active and passive range of movement can be caused by a vast array of conditions from rotator cuff tears, sub-acromial impingement or arthritis, all of which we have discussed in previous blogs on our website. Frozen shoulder however will present slightly differently in that both active and passive range of movement will be restricted in every direction as well as being relatively clear on radiograph (Abrassart et al. 2020).

Within the Richmond Rehab clinic the majority of our assessment of whether someone will present with true Frozen Shoulder will come from a thorough subjective examination and then a multi-plane active (you move your shoulder) and passive (we move your shoulder) examination.

Research suggests that the patients shoulder flexion and shoulder external rotation are the most commonly and most severely restricted motions with a restricted shoulder external rotation to either 50% of opposing side or less than 30 degrees of AROM (Jain et al. 2014) However this can vary and has been documented by Watson et al. 2000, to restrict abduction to less than 90 degrees and limit your hand behind back movement to around the lower lumbar vertebrae (Watson et al. 2000)

Phases

One of the most difficult parts of having a Frozen Shoulder is the sheer amount of time the condition lasts for, with symptom periods lasting anywhere from 18months onwards and residual symptoms beyond 2-3 years have been documented in studies that up to 15% will have long lasting symptoms (Buchbinder et al. 2008, Kraal et al. 2017)

Freezing: Painful initial phase which will generally last between 2-9 months, categorised by insideous diffuse disabling pain, felt worse at night and an inability to lie on the affected shoulder.

Frozen: An intermediate stiff phase that restricts your range of movement for around 4-12 months, where pain slightly decreases but an overwhelming stiffness and pain at the end of movement is common.

Thawing: The recovery phase, lasting roughly 5-24 months where range of movement gradually returns and activities of daily living become much easier.

(Buchbinder et al. 2008)

Pathology

The why behind this condition is possibly the hardest to give our patients a straight answer to. As mentioned above the underlying pathology behind why frozen shoulder occurs is debatable. Some research leans towards a process of inflammation whereas other research supports scarring of the capsule and even scarring as a result of inflammation (Hand et al 2007).

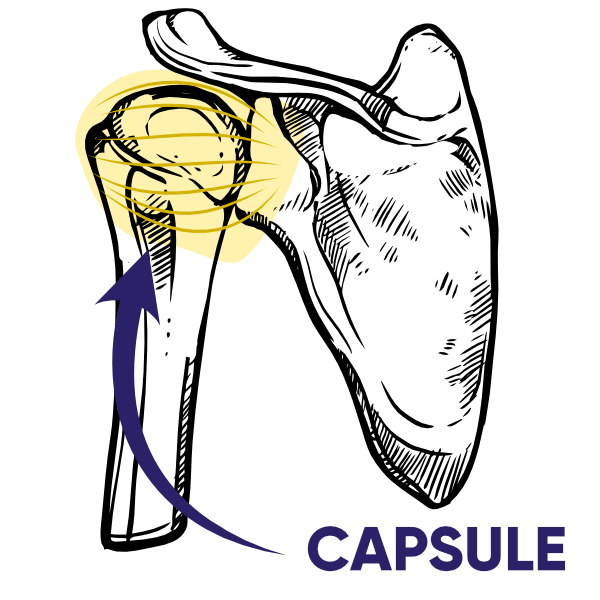

The capsule tissue around the ball and socket joint specifically localised to the coracohumeral ligament as shown in the picture below tends to be the primary affected area. On Frozen shoulder patients the tissue demonstrated inflammatory changes and fibrosis (scarring of the ligament fibres) (Hand et al. 2007).

What we do know is frozen shoulder causes severe pain and severe stiffness, however if we apply the phases above the stiffness outlasts the pain. Research leads toward an explanation of changes to blood circulation and its positive response to injections of corticosteroid, a potent suppressor of inflammation (Buchbinder, Green & Youd 2003).

Diabetes

As mentioned above there are small sub-groups of people on this planet that are just more susceptive to this condition. Patients that had both diabetes mellitus and clinically diagnosed Frozen Shoulder potentially were slower to resolve and more resistant to treatment (Hanchard et al. 2011). Other sub-groups that are classified as systemic are hyper and hypothyroidism as well as hypoadrenalism. Why this is the case is isn’t known definitively, along with other part of the Frozen shoulder process like why does the frozen shoulder spontaneously start thawing out. Research in the area points to certain “cytokines” of which can cause inflammation of the capsule or some that even inhibit production of other cells that limit contracture of soft tissue (Tania, Akatsu & Yano, 2014).

Treatment

The reported treatment strategies for frozen shoulder are broad and varied, from conservative measures such as exercise and mobilisation, to medication based strategies like oral or injected corticosteroid and even needling, massage and other complimentary therapies.

Jain & Sharma, 2014 looked at the various treatment strategies and the studies that tracked the improvement from them and has graded each in terms of effectiveness for improvement in 3 areas. This table is demonstrated below.

Grades of recommendations |

|

| Grade of recommendations for shoulder pain relief | |

Mobilisation (High grade) |

Grade A |

Therapeutic exercises |

Grade A |

Low level laser therapy |

Grade A |

Corticosteroid injection |

Grade B |

Acupuncture & exercises |

Grade B |

Electro-acupuncture & ITF |

Grade B |

Continuous passive motion |

Grade B |

Deep heat |

Grade B |

Ultrasound |

Not recommended |

| Grade of recommendations for imporement in shoulder range of motion | |

Mobilisation (High grade) |

Grade A |

Therapeutic exercises |

Grade A |

Corticosteroid injection & Physio |

Grade B |

Acupuncture & exercises |

Grade B |

Deep heat |

Grade B |

Dynasplint & Physio |

Grade C |

Low level laser therapy |

Not recommended |

Continuous passive motion |

Not recommended |

| Grade of recommendations for improvement in shoulder function | |

Mobilisation (High grade) |

Grade A |

Therapeutic exercises |

Grade A |

Acupuncture & exercises |

Grade B |

Low level laser therapy/p> |

Grade B |

Electro-acupuncture & IFT |

Grade B |

Deep heat |

Grade B |

Ultrasound |

Not recommended |

Continuous passive motion |

Not recommended |

Physiotherapy

A condition that consistently will come through the door at the Richmond Rehab clinic and one that is well suited for the skill set across the clinic, where conservative management has been seen in some studies to improve 60-80% of patients at long term follow up. (Sivasubramanian et al. 2020).

The treatment strategies that we employ here will usually consist of advice and education regarding the condition, its prognosis and likely course, exercise and stretching program as well as in some cases some manual manipulation.

When it comes to the education and advice to better the difficulty of every day tasks and the severity of pain, activity modification is important, such as tasks in the home, work and dependent on the severity even sporting and leisure activities. Physiotherapists can also discuss alternative ways to complete simple things such as sleeping positions, getting dressed or any other tasks so to not continually aggravate symptoms (Hanchard et al. 2011)

After we have assessed then educated the patient on their likely diagnosis and prognosis we will work through an independent exercise program to ensure their course is a little more bearable and hopefully on the faster end of the phase timelines mentioned above. Exercises such as rhythmic, low difficulty repetitive movements like a pendulum*[Picture] exercise can benefit pain and stiffness getting the shoulder girdle to somewhat relax. On the functions and mobility end, exercises such as passive, active and active assisted range of movement exercises*[Picture] to restore over time full mobility as well strength and resisted functional tasks to ensure as mobility returns the weakness gained over this time isn’t limiting your daily activity (Hanchard et al. 2011)

Massage & Manipulation

Massage/Acupuncture: Research and high level evidence for massage as a specific treatment strategy is lacking with low level evidence for an improvement in pain scores of patients early in their recovery period, however Liu et al. 2021 researched the effectiveness of massage and acupuncture for frozen shoulder in patients that also suffer from neck pain. Their study group compared cases of acupuncture only and a combination of acupuncture and massage, with improvement coming from both groups. With this poor level of evidence supporting the treatment strategy for this condition massage alone cannot be recommended for a recovery strategy to improve range of motion.

Manipulation Under Anaesthetic (MUA)

Usually saved for patients that when conservative management is “failing” so best believed to be undergone after 6-9 months of recovery. Studies are mixed between when the most effective time to apply this treatment strategy and even if the strategy itself is effective. The complications however can be vast and more serious in nature compared to treatment strategies teetering on the conservative side, these include humerus and glenoid fractures, rotator cuff tears, dislocations and injuries to the nerve tissue around the shoulder. (Cho, Bae, Kim, 2019)

Oral NSAIDs

Moving from the ultra conservative and non-invasive treatments such as physiotherapy and manipulation onto something a little more invasive but still easily accessible. Something I am sure a lot of us have reached for when we are dealing with some limiting pain, the simple anti-inflammatory tablet.

Buchbinder and associates looked at previous studies in this area and how the oral steroid can affect adhesive Capsulitis, in which they assessed five small trials with mid-level evidence. The main takeaway from this review was when compared against a placebo tablet the steroid based anti-inflammatory performed better, improving pain, range of movement and function, however beyond a 6 week period yielded no further results of this type.

Injections

Although increasing invasiveness injections are widely used for frozen shoulder patients and has been shown to be highly effective in improvement of symptoms and shoulder function as well as range of motion.

There are two types of injections administered:

Corticosteroid or “Cortisone” and Hydrodistention or Hydrodilitation being the more widely used injection for frozen shoulder patients where saline liquid and anaesthetic is injected into the joint to dilate the capsular tissue and stretch the tightened and adhered areas to allow for more glenohumeral movement (Tveita et al. 2008)

A corticosteroid injection is a targeted injection into the joint of a steroid based anti-inflammatory and has been shown to be of significant effect in shoulder pain compared to placebo and furthermore a short term benefit over physiotherapy on the short term (7 weeks) however at long term follow up patient function was similar (Buchbinder, 2003) Further review noted may improve pain at 3, 6 and 12 week follow up, demonstrating early injection as a reputable option early in recovery of frozen shoulder.

A recent overview of research on comparisons of the two injections came to the conclusion that a combination of the two improved pain scores, range of motion and function across the entirety of the 3 phases in comparison to a cortisone injection only and physiotherapy alone.

Surgery

When more conservative measures are ineffective for frozen shoulder patients surgical intervention may be indicated, with arthroscopic release being shown to have effective results in improving pain and function (Sivasubramanian et al. 2021). This particular review looked at the extent of the capsular release and how the outcomes compared when more extensive vs less extensive releases are completed. Their conclusion being that less extensive releases demonstrated better functional results and pain scores.

Mansat and associates in 2018, discussed surgical intervention being completed only if a flexion restriction to less than 100 degrees active range of movement is noted and is a discussion to be had with the surgeon, as generally improved motion comes at the expense of stability, strength and pain.